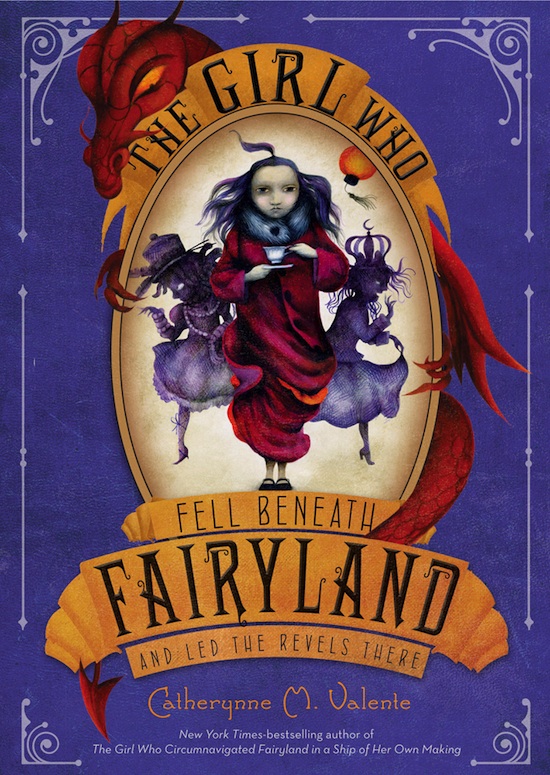

All this week we’re serializing the first five chapters of the long-awaited sequel to The Girl Who Circumnavigated Fairyland in a Ship of Her Own Making, Catherynne M. Valente’s first Fairyland book — The Girl Who Fell Beneath Fairyland and Led the Revels There is out on October 2nd. You can keep track of all the chapters here.

September has longed to return to Fairyland after her first adventure there. And when she finally does, she learns that its inhabitants have been losing their shadows—and their magic—to the world of Fairyland Below. This underworld has a new ruler: Halloween, the Hollow Queen, who is September’s shadow. And Halloween does not want to give Fairyland’s shadows back.

Fans of Valente’s bestselling, first Fairyland book will revel in the lush setting, characters, and language of September’s journey, all brought to life by fine artist Ana Juan. Readers will also welcome back good friends Ell, the Wyverary, and the boy Saturday. But in Fairyland Below, even the best of friends aren’t always what they seem. . . .

CHAPTER III

THE REINDEER OF MOONKIN HILL

In Which September Considers the Problem of Marriage, Learns How to Travel to the Moon, Eats Fairy Food (Again), Listens to the Radio, and Resolves to Mend Fairyland as Best She Can

September hugged her elbows. She and Taiga had been walking for some time without speaking. The stars had trudged down toward dawn in their sparkling train. She wanted to talk—the talk boiled inside her like a pot left on just forever with no one minding it. She wanted to ask how things in Fairyland had gone since she’d left. She wanted to ask where she was relative to the Autumn Provinces or the Lonely Gaol—north, south? A hundred miles? A thousand? She even wanted to throw her arms around the deer-girl, who was so obviously magical, so clearly Fairylike, and laugh and cry out, Do you know who I am? I’m the girl who saved Fairyland!

September blushed in the dark. That seemed suddenly a rather rotten thing to say, and she took it back without ever having uttered the thing. Taiga kept on as the land got hillier and the glass trees began to get friends of solid, honest wood, black and white. She said nothing, but she said nothing in a particularly pointed and solemn and deliberate way that made September say nothing, too.

Finally, the grass humped up into a great hillock, looking quite like an elephant had been buried there—and not the runt of its litter, either. Big, glossy fruits ran all over the hill, their vines trailing after them. September could not tell what color they might be in the daytime—for now they glowed a shimmery, snowy blue.

“Go on, have one,” Taiga said, and for the first time she smiled a little. September knew that smile. It was the smile a farmer wears when the crop is good and she knows it, so good it’ll take all the ribbons at the county fair, but manners say she’s got to look humble in front of company. “Best moonkins east of Asphodel, and don’t let anyone tell you different. They’ll be gone in the morning, so eat up while they’ve got a ripening on.”

September crawled partway up the hill and found a small one, small enough that no one might call her greedy. She cradled it in her skirt and started back down—but Taiga took a running start and darted past her, straight to the top. She sprang into the air with a great bounding leap, flipped over, and dove right down into the earth.

“Oh!” September cried.

There was nothing for it—she followed Taiga up the hill, making her way between giant, shining moonkins. Glassy vines tangled everywhere, tripping up her feet. When she finally reached the crest, September saw where the deer-girl had gone. Someone had cut a hole in the top of the hill, a ragged, dark hole in the dirt, with bits of root and stone showing through, and grass flowing in after. September judged it big enough for a girl, though not for a man.

Much as she would have liked to somersault and dive like a lovely gymnast, headfirst into the deeps, September did not know how to flip like that. She wanted to, longed to feel her body turn in the air that way. Her new, headless heart said, No trouble! We can do it! But her sensible old legs would not obey. Instead, she put her pale fruit into the pocket of her dress, got down on her stomach, and wriggled in backward. Her bare legs dangled into whatever empty space the hill contained. September squeezed her eyes shut, holding her breath, clutching the grass until the last moment—and popped through with a slightly moist sucking noise.

She fell about two feet.

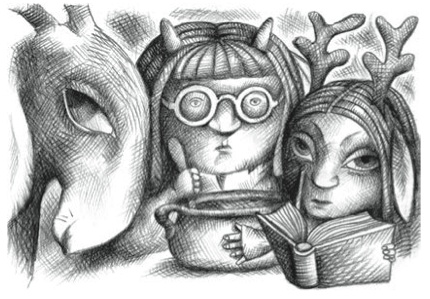

September opened her eyes, first one, then the other. She was standing on a tall bookcase, and just below it stood a smaller one, and then a smaller one again, and another, and another, a neat little curving staircase of books down from the cathedral ceiling of the moonkin hill. Down below, several girls and boys like Taiga paused in their work to look up at the newcomer. Some of them wove lichen fronds into great blankets. Some of them boiled a creamy stew full of moonkin vines that smelled strange but not unpleasant, like peppermint and good thick potatoes. Some had on glasses and worried away at accountants’ books, some refilled the oil in pretty little lamps, some relaxed, blowing smoke from their pipes. The coziness of the scene quite overpowered September, whose feet and fingers still tingled with numb coldness. Here and there peeked everything that made a house feel alive, paintings on the walls and rugs on the floor and a sideboard with china and an overstuffed chair that didn’t match anything else. Everyone had very delicate, very bare feet.

“I daresay doors are more efficient.” September laughed as she made her way down. “They aren’t hard to make, either. Not much more than a hinge and a knob.”

Taiga held up a hand to help September off of the last shelf.

“Hunters can use doors. This way we’re safe.”

“You keep talking about hunters! We didn’t see one on the way here and really, I can’t believe someone would hunt a girl! I don’t think girls make very good roasts or coats.”

“They don’t want to kill us,” Taiga said darkly. “They want to marry us. We’re Hreinn.”

September bit her lip. Back home, she had gotten used to knowing things no one else knew. It was a nice feeling. Almost as good as having a secret. Now she was back in the country of never knowing anything.

Taiga sighed. She took off her boots and her gloves and her coat and folded them neatly onto the mismatched chair. She took a deep breath, then tugged on her deer-ears. Her whole body rolled up like a shade suddenly drawn—and then standing before September was not a girl but a smallish reindeer with black fur and white spots on her forehead, a big, wet nose, and big, fuzzy, heavy antlers. She was somewhat shorter than September expected a reindeer would be, big enough to look her in the eye, but not to make her feel afraid. Yet Taiga was not cuddly or sweet like a Christmas reindeer in a magazine—rather, muscles moved under her skin, and everything in her lean, graceful shape said speed and strength and a feral kind of thrill in biting things. Taiga turned her head and caught her ear in her teeth, yanking on it savagely, and her sleek reindeer-self rolled down into a dark puddle. The girl with white hair and black ears stood before September again.

And then, slowly, Taiga pulled the puddle into her arms. It was black and furry. She held it lovingly.

“This is my skin, you see,” Taiga whispered. “When we’re human, we have this little bit of reindeer left over. Not just deer, you know. Deer are gossips and prank-pullers and awful thieves. Reindeer. Hreinn. Reindeer aren’t from around here, you know. We come from the heavens—the moon is our motherland.”

“But no one can live on the moon!” said September. “It’s too cold and there’s no air. I’m in the astronomy club, and Miss Gilbert was very specific about that.”

“Then I’m sorry for your moon—what a poor, sad planet! We will set a place for her at dinner, out of respect. Our moon is rich and alive. Rice fields and moonkin meadows as far as you can see. And Hreinn like moss spores, so many and scattered so far. And hunters. All kinds—Fairies, Satyrs, Bluehearts, Ice Goblins. Once the moon was generous enough for all of us. In our reindeer-bodies, we ran and hid from pelt traders and hungry bowmen. That was fine. That’s how the moon plays her hand—she’s a tough, wild matron. We eat and they eat. Grow fleet and clever went our lullabies. Escape the hunter’s pot today, set your own table tomorrow. But once the huntsmen saw us change, they knew our secret, and they wanted more than stew. They stole our skins and hid them away, and when a body has your skin, you have to stay and cook and clean and make fawns for them until they get old and die. And sometimes then you still can’t find your skin, and you have to burn the cottage down to catch it floating out of the ash. They chased us all the way down the highway to Fairyland, down from the heavens and into the forest, and here we hide from them, even still.”

“You’re cooking and cleaning now,” September said shyly. A Hreinn boy looked up from kneading dough, his pointed ears covered in flour. She thought of the selkies she’d read about one afternoon when she was meant to be learning about diameters and circumferences: beautiful seals with their spotted pelts, turning into women and living away from the sea. She thought of a highway to the moon, lit with pearly streetlamps. It was so wonderful and terrible her hands trembled a little.

“We’re cooking for us to eat. Cleaning for us to enjoy the shine on the floor,” Taiga snapped. “It’s different. When you make a house good and strong because it’s your house, a place you made, a place you’re proud of, it’s not at all the same as making it glow for someone who ordered you to do it. A hunter wants to eat a reindeer, just the same as always. But here in the Hill we’re safe. We grow the moonkins and they feed us; we love the forest and it loves us in its rough way—glass shines and cuts and you can’t ask it to do one and not the other. We mind our own, and we only go to Asphodel when we need new books to read. Or when a stranger tromps around so loudly someone has to go out and see who’s making the racket.”

September smiled ruefully. “I suppose that’s my racket. I’ve only just arrived in Fairyland, and it’s hard to make the trip quietly.” She hurried to correct herself, lest they think she was a naive nobody. “I mean to say, I’ve been before, all the way to Pandemonium and even further. But I had to go away, and now I’m back and I don’t want to trouble you, I can clean my own floors quite well even if I complain about it. Though I think I would complain even if it were my own dear little house and not my mother and father’s, because on the whole I would always rather read and think than get out the wood polish, which smells something awful. I honestly and truly only want to know where I am—I’m not a hunter, I don’t want to get married for a long while yet. And anyway where I come from if a fellow wants to marry a girl, he’s polite about it, and they court, and there’s asking and not capturing.”

Taiga scratched her cheek. “Do you mean to say no one pursues and no one is pursued? That a doe can marry anyone she likes and no one will leap on her in the night to make the choice for her? That if you wanted you could live by yourself all your life and no one would look askance?”

September chewed the inside of her lip. She thought of Miss Gilbert, who taught French and ran the astronomy club, and how there had been quite the scandal when she and Mr. Henderson, the math teacher, meant to run off together. The Hendersons had good money and good things, big houses and big cars, and he only taught math because he liked to do sums. Mr. Henderson’s family had forbidden the whole business. They’d found a girl all the way from St. Louis with lovely red hair for him and told the pair of them to get on with the marrying. Miss Gilbert had been heartbroken, but no one argued with the Hendersons, and that was when the astronomy club had gotten started. The Hendersons were hunters, and no mistaking, they’d snuffed out that St. Louis belle with a quickness. Then September thought of poor Mrs. Bailey, who had never married anyone or had any babies but lived in a gray little house with Mrs. Newitz, who hadn’t married either, and they made jam and spun yarn and raised chickens, which September considered rather nice. But everyone clucked and felt sorry for them and called it a waste. And Mr. Graves who had chased Mrs. Graves all over town singing her love songs and buying her the silliest things: purple daisies and honeycomb and even a bloodhound puppy until she took his ring and said yes, which certainly seemed like a kind of hunting.

But still, September could not quite make the sums come out right. It was the same, but not the same at all. Because she also thought of her mother and father, how they had met in the library on account of them both loving to read plays rather than watch them. “You can put on the most lavish productions in your head for free,” her mother said. Perhaps, if hunting had occurred, they had hunted each other through the stacks of books, sending warning shots of Shakespeare over one another’s heads.

“I think,” she said slowly, adding and subtracting spouses in her head, “that in my world, folk agree to a kind of hunting season, when it comes to marrying. Some agree to be hunted and some agree to be hunters. And some don’t agree to be anything at all, and that’s terribly hard, but they end up knowing a lot about Dog Stars and equinoxes and how to get all the seeds out of rose hips for jelly. It’s mysterious to me how it’s worked out who is which, but I expect I shall understand someday. And I am positively sure that I shall not be the hunted, when the time comes,” September added softly. “Anyway, I’d never hunt you—I wouldn’t even have taken a bite of your crop if you hadn’t invited me. I just want to know where I am and how far it is to Pandemonium from here, and how long it’s been since I left! If I were to ask about the Marquess, would you know who I meant?”

Taiga whistled softly. Since the reindeer-maid had shown her skin and not been immediately whisked off to a chapel, several of the Hreinn had deemed September safe. They rolled up into reindeer and now lay about, showing their soft sides and beautiful antlers. “That was a bad bit of business,” Taiga said, rubbing her head.

“Yes, but . . . ancient history or current events?” September pressed.

“Well, last I heard she was up in the Springtime Parish. I expect she’ll stay there a good while. Neep and I”—she gestured to the flourspeckled boy—“we went to the pictures in town once and saw a reel about it. She was just lying there in her tourmaline coffin with her black cat standing guard and petals falling everywhere, fast asleep, not a day older than when she abdicated.”

“She didn’t abdicate,” September said indignantly. She couldn’t help it. That wasn’t how it had gone. Abdication was a friendly sort of thing, where a person said they didn’t want to rule anything anymore so suds to this and thank you kindly. “I defeated her. You won’t believe me, but I did. She put herself to sleep to escape me sending her back where she came from. I’m September. I’m . . . I’m the girl who saved Fairyland.”

Taiga looked her up and down. So did Neep. Their faces said, Go on, tell us another. You can’t even turn into a reindeer. What good are you?

“Well, I guess it was a few years ago now, to answer your question,” Taiga said finally. “King Crunchcrab made a holiday. I think it’s in July.”

“King Crunchcrab? Charlie Crunchcrab?” September shrieked with delight at the name of the ferryman who had once, not very long ago, steered the boat that brought her into Pandemonium.

“He doesn’t like us calling him that, really,” Neep hushed her. “When he gets on the radio he tells us, ‘Ain’t a Marquis and ain’t a King, and can’t somebody get these frippering dresses out of my closet, hang you all.’ Still, he’s a good sort, even if he grumbles about having to wear the tiara. Folk thought a Fairy should move into the Briary, after everything. He was the only one they could catch.”

September sank into a coffee-colored sofa. She folded her hands and braced herself to hear what she suspected would follow, but hoped would not. “And the shadows, Taiga? What about the shadows?”

Taiga looked away. She went to the soup and stirred vigorously, scraping bits of savory crust from the pan and letting them float to the top. She filled a bowl and thrust it at September. “That won’t hear out on an empty stomach. Eat, and crack your moonkin, too, before the sun comes up. They’re night beasts. They wilt.”

For a moment, September did not want to. She was overcome by the memory of fearing Fairy food, trying to avoid it and starve bravely, as she had done before when the Green Wind said one bite would keep her here forever. It was instinct, like jerking your hand away from fire. But, of course, the damage had long been done, and how glad she was of it! So September did eat, and the stew tasted just as it smelled, of peppermint and good potatoes, and something more besides, sweet and light, like marshmallows, but much more wholesome. It should have tasted foul, for who ever heard of mixing such things? But instead it filled September up and rooted her heart right to the earth where it could stand strong. This flavor was even better: like a pumpkin but a very soft and wistful sort of pumpkin who had become good friends with fresh green apples and cold winter pears.

Finally Taiga took her bowl and clicked her tongue and said, “Come to the hearth, girl. You’ll see I wasn’t keeping things from you. I only wanted you to eat first, so you’d have your strength.”

All the Hreinn drew together, some in reindeer-form and some in human, at the far edge of the long hill-hall. A great canvas-covered thing waited there, but no fire or bricks or embers. Neep pulled back the cloth—and a radio shone out from the wall. It looked nothing like the walnut radio back home. This one was made of blackwood branches and glass boughs, some of them still flowering, showing fiery glass blossoms, as though the sun somehow still shone through them. The knobs were hard green mushrooms and the grille was a thatch of carrot fronds. Taiga leaned forward and turned the mushrooms until a crackle filled the air, and the Hreinn drew close to hear.

“This has been the Evening Report of the Fairyland News Bureau,” came a pleasant male voice, young and kind. “Brought to you by the Associated Pressed Fairy Service and Belinda Cabbage’s Hard-Wear Shoppe, bringing you all the latest in Mad Scientific Equipment. We here at the Bureau extend our deepest sympathies to the citizens of Pandemonium and especially to Our Charlie, who lost their shadows today, making it six counties and a constablewick this week. If you could see me, loyal listeners, you’d see my cap against my chest and a tear in my eye. We repeat our entreaty to the good people of FairylandBelow, and beg them to cease hostilities immediately. In other news, rations have been halved, and new tickets may be collected at municipal stations. Deep regrets from King C on that score, but now is not the time to fear, but to band together and muddle through as best we can. Keep calm and carry on, good friends. Even shadowless we shall persevere. Good night, and good health.”

A tinny tune picked up, something with oboes and a banjo and a gentle drum. Taiga turned the radio off.

“It’s meant to tune itself to you, to find the station that has the tune or the news you want to hear. Cabbage-made, and that’s the best there is.” Taiga patted September’s knee. “It’s Fairyland-Below, everyone knows it. Shadows just seep into the ground and disappear. They’re stealing our shadows, and who knows why? To eat? To murder? To marry? To hang on their walls like deer heads? Fairyland-Below is full of devils and dragons, and between them all they’ve about half a cup of nice and sweet.”

September stood up. She brushed a stray moonkin seed from her birthday dress. She looked once upward, and her heart wanted her friends Ell, the Wyverary, and Saturday, the Marid, with her so badly she thought it might leap out of her chest and go after them, all on its own. But her heart stayed where it was, and she turned her face back toward Taiga, who would not be her friend after all, not now, when she had so far yet to go. “Tell me how to get into Fairyland-Below,” September said quietly, with the hardness of a much older girl.

“Why would you go there?” Neep said suddenly, his voice high and nervous. “It’s dreadful. It’s dark and there’s no law at all and the Dodos just run riot down there, like rats. And . . .” he lowered his voice to a squeak, “the Alleyman lives there.” The other Hreinn shuddered.

September squared her shoulders. “I am going to get your shadows back, all of you, and Our Charlie, too. And even mine. Because it’s my fault, you see. I did it. And you must always clean up your own messes, even when your messes look just like you and curtsy very viciously when what they mean is, I am going to make trouble forever and ever.”

And so September explained to them about how she had lost her shadow, how she had given it up to save a Pooka child and let the Glashtyn cut it off her with a terrible bony knife. How the shadow had stood up just like a girl and whirled around in a very disconcerting way. She told Taiga and Neep and the others how the Glashtyn had said they would take her shadow and love her and put her at the head of all their parades, and then all of them dove down to the kingdom under the river, which was surely Fairyland-Below. Though she could not quite work it out, September felt sure that her shadow and everyone’s shadows were all part of the same broken thing, and broken things were to be fixed, whatever the cost, especially if you had been the one to break it in the first place. But September did not tell them any more about her deeds than she had to. When it came down to it, even if hearing that she was good with a Fairy wrench might have made them more sure of her, she could not do it. It was nothing to brag about, when she had left Fairyland so upset in the doing of it. She begged them again to tell her how to get down to that other Fairyland; she would risk the hunters that ran so rampant in the forest.

“But September, it’s not like there’s a trapdoor and down you go,” insisted Taiga. “You have to see the Sibyl. And why do that, why go see that awful old lady when you could stay here with us and eat moonkins and read books and play sad songs on the root-bellows and be safe?” The reindeer-girl looked around at her herd and all of them nodded, some with long furry faces, some with thin, worried human ones.

“But you must see I can’t do that,” September said. “What would my Wyvern think of my playing songs while Fairyland was hurting? Or Calpurnia Farthing the Fairy Rider or Mr. Map or Saturday? What would I think of myself, at the end of it all?”

Taiga nodded sadly, as if to say, Arguing with humans only leads to tears. She went to one of the bookshelves and drew out a large blue volume from the top shelf. She stood on her tiptoes.

“We’ve been saving it,” she explained. “But where you’re going you’ll need it more.”

And she opened the midnight covers. Inside, like a bookmark, lay a thin and beautifully painted square notepad with two sheaves left inside, the rest ripped out and used up long ago. Its spine shone very bright against the creamy pages, its edges filigreed with silver and stars. It read:

MAGIC RATION BOOK

MAKE DO WITH LESS, SO WE ALL CAN HAVE MORE.

The Girl Who Fell Beneath Fairyland and Led the Revels There © Catherynne M. Valente 2012